افسانه جیپی و GP

دکتر بابک شکوهی

در سالهای اخیر آشنایی با دیگر فرهنگها و دیگر سامانههای اقتصادی، درمانی، آموزشی و… امری بدیهی و لازمالاجرا برای مدیریت بهینه منابع شده است. یکی از موارد تفاوت سیستم، در نامگذاری افراد یا سمتها، بسیار چشمگیر است؛ بهطوری که در چند ماهه اخیر نگارنده شاهد سوءتفاهمهای بسیار، حتی در مقولات علمی و در سطوح بالای جامعه بوده است. در همین زمینه، نگارنده مشاهدات خود را بهصورت گزارشی از سیستم آموزش پزشکی خانواده در انگلستان و کشورهای مشترکالمنافع و مقایسه آن با دیگر کشورهای غربی ارایه میدهد با این امید که آشنایی بیشتر با این سیستم و نامگذاری سمتهای گوناگون در آن برای همکاران و هموطنان بهگونهای روشنتر نمود کند.

معمولاً دانشآموزان انگلیسی در سن ۱۸ سالگی وارد سیستم آموزشی پزشکی میشوند. برای ورود به دانشگاه کنکور سراسری وجود ندارد؛ ولی برخی دانشگاهها آزمونهایی را برای سطحبندی داوطلبین خود برگزار میکنند. دانشآموزان بر اساس نمرههای سال آخر آموزشی (A-Level) میتوانند به پذیرش در دانشگاهها امیدوار باشند. از آنجایی که تعداد دانشگاههایی که میتوانند انتخاب کنند محدود است، بر اساس نمرات پذیرششده سالهای قبل، دانشآموزان به انتخاب رشته و دانشگاه میپردازند. پس از گزینش و پذیرش اولیه، با دانشآموزان مصاحبه حضوری صورت میگیرد.

پیش از سال ۲۰۰۷

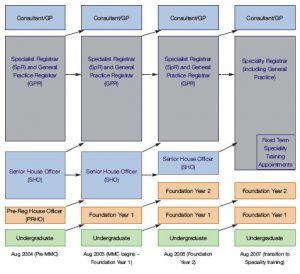

در هر صورت، طول دوره آموزش پزشکی بهطور معمول ۶ سال بوده و متعاقباً یک سال هم دوره PRHO یا Pre-registration House Officer که معادل دوره انترنی در ایران است، برای همه اجباری است. بهطور تاریخی، آموزش پزشکی بعد از این مرحله بهصورت غیرمتمرکز و در بیمارستانهای گوناگونی صورت میگرفت. تا پیش از سال ۲۰۰۷ میلادی، پزشکانی که با پایان دوره PRHO در نظام پزشکی (GMC) ثبتنام شده بودند، به جستجوی شغلهای ۶ ماهه بهعنوان SHO یا Senior House Officer میپرداختند و بهندرت مشاغل گردشی (Rotation or Fixed-Term) دو یا سه ساله نیز موجود بود. در این خلال، رشتههای مختلف در شغلهای ۶ ماهه انتخاب میکردند و بر اساس تخصصهایی که در آینده برمیگزیدند و با مشورت اساتید راهنما و مشاور، پس از طی ۴ دوره ۶ ماهه و گذراندن قسمت کتبی امتحان کالج سلطنتی مربوطه، برای شغلهای Registrar و دریافت یک شماره CCT اقدام میکردند. کسانی که بیش از ۴ شغل ۶ ماهه فعالیت داشتند یا کسانی که بخشی آر آموزش آنها در کشورهای غیر از انگلستان صورت گرفته بود، به اداره بورد مربوطه و کالج سلطنتی مربوطه ارجاع داده میشدند تا درباره طول دوره ایشان تصمیمگیری شود.

گروه اول که دوره پزشکی و سه سال ابتدایی بعد از فارغالتحصیلی را در انگلستان میگذراندند، پس از اتمام دوره Registrar، بر اساس بند شماره ۱۰ آموزش پزشکی تخصصی، مدرکی دریافت میکردند به نام CCT یا Certificate of Completion of Training و کسانی که در گروه دوم قرار داشتند بر اساس بند شماره ۱۱ آموزش پزشکی تخصصی، مدرکی دریافت میکردند به نام CEE یا Certificate of Equivalent Experience. هر دو این مدارک برای اداره بورد تخصصی و کالجهای سلطنتی مربوطه ارزشی یکسان دارد و با این مدارک، پزشکان درخواست درج در فهرست متخصصین نظام پزشکی میکنند.

در هر صورت آنچه در ایران جیپی نامیده میشود، در واقع SHO است و آنچه در انگلستان GP نامیده میشود، در واقع متخصص پزشکی خانواده است که معمولاً یک دوره سهساله را گذرانده و در سال آخر تحصیل خود، Registrar نامیده میشده است.

لازم به ذکر است که عضویت در کالج سلطنتی GP تا سال ۲۰۰۷ میلادی امری اختیاری بود و بهدلیل اینکه عضویت در این کالج مستلزم شرکت در امتحانات و صرف هزینه بود، بسیاری از GPهای شاغل در انگلستان عضویت در این کالج را نداشتند. در واقع اکثراً کسانی به عضویت کالج سلطنتی درمیآمدند که قصد کار دانشگاهی و آموزشی داشتند، به نحوی که میتوان عضویت در کالج سلطنتی را معادل بورد تخصصی تعبیر کرد چرا که بدون آن شرکت در فعالیتهای آموزشی میسر نبود.

نکته شایان ذکر دیگر اینکه در سیستم انگلستان به پزشکان ریز نمرات داده نمیشود و معمولاً استادان مربوطه امتحانی هم بهصورت مدون برگزار نمیکنند. ارزیابی پزشکان عمدتاً بهصورت آموزش و سنجش ضمن خدمت انجام میشود و امتحانات اصلی در واقع امتحانات بورد و امتحانات عضویت در کالج سلطنتی مربوطه است.

بعد از سال ۲۰۰۷

از سال ۲۰۰۷ به بعد، شکل جدیدی به آموزش تخصصی داده شد. دو سال بهعنوان Foundation Years بهجای PRHO و SHO سال اول و بهطور اجباری برای همه پزشکان به دوره آموزشی اضافه شد. در واقع بخشی از آموزش لازم برای فارغالتحصیلی در رشته پزشکی در نظر گرفته شد. هر یک از این دورهها شامل سه بخش ۴ ماهه است که برای همه رشتهها ۴ ماه در مطب پزشکان (بهعنوان Primary Care) برای همه الزامی و اجباری است. پزشکانی که مایل به ادامه تحصیل و گرفتن تخصص در GP هستند، یک بخش ۴ ماهه اضافه در GP در خلال این دو سال خواهند داشت. در این زمان پزشکان در حالی که آخرین بخش ۴ ماهه خود را میگذرانند، برای دورههای مورد نظر خود در ۳ سال آینده درخواست کار میدهند. هماکنون در انگلستان انواع انگشتشماری از دورههای گردشی وجود دارد که پرتعدادترین آنها عبارتاند از:

- Core Medical Training

- Core Surgical Training

- GP Training

متعاقب این دورهها که معمولاً ۳ ساله است، همه پزشکان در امتحانات کالج سلطنتی مربوطه شرکت و خود را برای سال/ سالهای Registrar آماده میکنند. در حال حاضر، دورههای تخصصی داخلی و جراحی، همه به دورههایی میانجامند که ما در ایران «فوقتخصص» مینامیم و ۵ تا ۶ سال به طول میانجامند. دوره GP که در واقع پزشکی خانواده است، در حال حاضر ۳ ساله و در آینده نزدیک ۴ ساله خواهد بود.

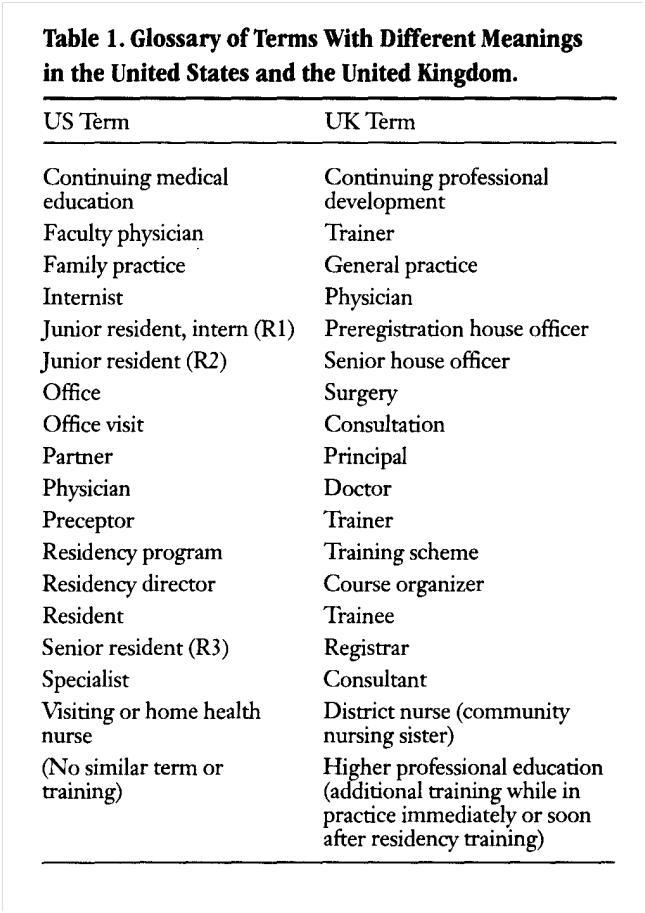

با امید اینکه این توضیحات مفید واقع شود؛ بهمنظور حسنختام اصطلاحات مربوطه در سامانههای انگلیسی و آمریکایی در جدول زیر نمایش داده شده است.

Onion DK, et al, ABFP March-April 1999 Vol. 12 No.2, 162-172

Onion DK, et al, ABFP March-April 1999 Vol. 12 No.2, 162-172

Appendix

The Foundation Programme is a two-year structured programme of workplace-based learning for junior doctors that forms a bridge between medical school and specialty training. The programme aims to provide a safe, well-supervised environment for doctors to put into practice what they learned in medical school. It provides them with the generalist medical knowledge and skills to meet the requirements of the General Medical Council (GMC) The New Doctor (2007) and the Foundation Programme Curriculum (2007) and prepares them for entry into specialty training. All medical graduates must undertake, and complete the Foundation Programme in order to work as a doctor in the UK.

The programme was first proposed by England’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Sir Liam Donaldson in 2002 in his document Unfinished Business and replaces the old Pre-Registration House Officer year and the first year of the Senior House Officer grade. Introduced as part of a series of initiatives under the Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) umbrella, the programme aims to ensure that foundation doctors develop and enhance their clinical and generic skills at the same time as exploring a range of career options.

An insider’s view of the American and UK medical systems

The similarities between UK and American medicine are greater than the differences but not quite as interesting.

This article will describe the US medical education system, some of the differences between UK general practice and US family medicine, US health insurance and doctors’ compensation, and discuss some of the shortcomings and advantages when compared to the UK system.

American children finish high school at 17 or 18 years old. They get a diploma rather than A and O levels. Only those planning on further education take national exams and most of these are general rather than subject specific.

Those who become doctors complete a 4-year general programme to get a Bachelor of Arts or Sciences (BA or BS) prior to attending medical school, which is a further 4 years including 2 years of classroom sciences and 2 years of wardbased training in most of the specialties. They graduate with the Doctor of Medicine (MD) degree at 25 or more years old.

During and after medical school, US doctors (and doctors emigrating to the US) take the US Medical Licensure Exam (USMLE) in three parts. During the 4th year of medical school they apply to their desired residency training programmes and learn their assignment for the next 1–۶ years at ‘Match Day’. Any candidates not selected participate in a mad scramble for unfilled posts. Few doctors start or end a programme at any time other than 1 July of each year and in most residency programmes a doctor remains in the same programme until completion, performing most training at the same hospital or complex of hospitals in one town.

However, there are some pyramid systems. Some specialties such as anaesthesia otolaryngology (ENT) or urology do not provide an integral post- 60 British Journal of General Practice, January 2006 graduate year 1 (PGY-1) or internship so applicants are expected to do a ‘categorical’ or surgical internship prior to PGY-2 and onward in the final specialty.

There are also those who change their minds or are put out of a programme for educational or other reasons. These doctors — once any suitability to practice issues are resolved — can apply to other specialty residencies and hope to have some of their prior training accepted in the new programme. Prior to any ‘registration’ — called licensure and offered by the individual states so requirements vary — doctors must complete a minimum of 2 years of postgraduate (residency) training (except those already licensed under older laws).

Residency length varies from 3 years — PGY-1, 2, and 3 — for family medicine, internal (general) medicine, or paediatrics, up to 5–۶ years for general surgery. Sub-specialties such as transplantation surgery may involve 6 years general surgery, a 2- to 3-year chest surgery fellowship followed by 3 or more years of transplant surgery fellowship. Medical subspecialty training such as nephrology or gastroenterology is obtained through fellowships following internal medicine or paediatric residencies.

Doctors take exams after finishing their residency to become accredited by the board of their specialty. Some of these exams are multiple choice questions, while others include oral examinations or evaluation of patient charts or operative notes. In some specialties the final board exams cannot be taken until the doctor has completed a certain number and variety of surgical procedures. In most specialties doctors repeat the exams every few years — every 6–۷ years for family medicine.

Family medicine is the closest thing to general practice in the US. The 3-yearresidency is usually performed with no moving, the same classmates, patients, hospital (except for away rotations), and consultants. The trainers are the hospital’s consultants and dedicated family medicine doctors with a practice attached to the training hospital who are also family medicine hospital consultants (qualified to care for inpatients and deliver babies). Training includes 10 months with adult inpatients, including 3 months in an intensive care unit (ICU) or coronary care unit, 7 months with paediatrics inpatients including neonatal ICU, and 4 months in obstetrics and gynaecology. These courses are not in consecutive 6 month blocks but in 1- or 2-month rotations spread throughout the 3 years so the resident has training with increasing responsibility. They also complete between 0.5 to 2 months each of surgery, outpatient cardiology, dermatology, orthopaedics, psychiatry and other specialties.

During the 3 years the trainee conducts family medicine surgeries at the training programme’s group practice close to (or in) the hospital with a panel of families (number increasing each year) assigned to them (but seeing the other doctors in practice when the trainee is not available). For the 1st year, this is one (half-day) surgery per week; the 2nd year three surgeries per week; and in the final year one half-day surgery every weekday.

The trainee is precepted during these surgeries by rotating members of the family medicine teaching staff. There are 7 hours a week of protected teaching time; attendance is mandatory nd patient care is never allowed to prevent attendance. Some residency programmes are at hospitals or medical centres with other residency programmes, and in this case some residents complete group training, whereas other residents are on their own at a smaller hospital with (usually) a lower intensity ICU experience.

The residents perform at least 50 normal British Journal of General Practice, January 2006 61 vaginal deliveries and are qualified to deliver babies when they finish, but must maintain this skill to obtain permission to deliver babies at any given hospital where they eventually work. While many family medicine doctors give up delivering babies, most of them (although this number is dropping) provide hospital care to their patients when needed. There is a move to concentrate this work in hired hospitalists (sometimes not family medicine doctors) or by having one doctor in turn from a group practice do all the hospital care for a week or 2 weeks. A typical family doctor has surgeries 9–۱۲ am and 1–۵ pm and visits patients in hospital (if any) once or twice daily, usually before/after the day of surgeries.

Appointments are 15 minutes long (plus urgent overbookings) and a nurse assistant prepares patients by assessing blood pressure, weight, or other vitals and preparation beforehand. The surgery has two to three exam rooms per doctor and patients wait inside, undressed if appropriate, while the doctor rotates through the rooms. More serious discussions may occur in the doctor’s office.

There are almost no home visits. Insurance companies will not pay for a home visit unless the patient is chronically unable to leave the home. Those who are severely ill — in UK practice ‘too ill to come into the surgery’ — are thought to need evaluation at the emergency room (ER) since they may need admission or acute tests. They can be seen by an emergency medicine doctor or, by arrangement, their family doctor (after office hours) or the doctor on call for their doctor.

Family doctors cover out-of-hours in many ways. They are deemed to have a responsibility to their patients but the availability of ER care keeps this from being a medicolegal responsibility. Some Reportage doctors even delegate out-of-hours care to freestanding urgent care centres. Doctors with admitting privileges at a hospital have a duty to the hospital to cover their patients’ hospital care. This frequently means they have to admit those deemed needing care by ER staff, and rotate coverage of admissions for patients with no doctor (or no doctor with hospital admitting privileges). In ERs with doctors on duty the ER doctor may admit initially, but the family doctor assumes care in the morning. ‘On call’ also means fielding patient telephone calls. Coverage is usually shared with other doctors either in the same group or across groups and only rarely are singlehanded doctors personally available to their patients 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Doctors earn money for the specific work they do and there is a great deal of documentation for each consultation or hospital care encounter and some thinking involved in deciding the level of care provided and the diagnosis treated (to ensure it is covered by the insurer). Errors are penalised by underpayment or fines if overcharging is detected. This data, either paper or electronic, is used by the (multiple) insurance companies to pay the doctors. While this is private practice, unless the insurer is the government (Medicare or Medicaid), the insurance companies pressure doctors to accept lower fees if they wish to be permitted to have the insurer’s covered patients attend at their surgery and the fees are lower than the doctors would prefer to charge, and, relatively, it is not as lucrative as UK private practice.

US medical economics is in flux in comparison to the NHS. It still has economic features of a purely capitalist driven system — some specialties get much better pay — but the only truly private practice (paid for by the patient) is infertility and cosmetic surgery care.

Waiting times are much less than in the NHS for most procedures and consultants if the patient has insurance 62 British Journal of General Practice, January 2006 accepted by the consultant or will pay cash ahead of time, but there is still a slight wait (a few weeks for non-urgent appointments in most areas) to see consultants — presumably because medicine in the US is no longer so lucrative that there is a relative surplus of specialists (due to insurance companies’ downward pressure on fees). For patients without insurance, or whose lower paying insurance coverage is not accepted by the consultant, the wait may be years until a consultant, if any, providing charity procedures or appointments has an opening in that schedule. Forty-five million (or about 20%) of Americans are uninsured. This means that if they attend a doctor’s surgery they will be charged $40–۲۰۰ (or more) for the visit, will have to pay full price for any prescriptions, and if hospitalised will have large hospital bills. They are often billed at a higher rate than the insurance company will pay for the same type of care. This group overlaps with the very poor — some of this group would qualify for low income health insurance administered by each state (Medicaid) if they were aware and knew how to apply — and with those who are able to afford health insurance but opt not to purchase it. Affordability is relative: health insurance for a healthy family of four would cost about $4000–۶۰۰۰ a year with no coverage of pregnancies, and those paying this much in rent or earning only $20 000 a year, might feel that is too much to pay. Personally, at my income level, I would ensure that my children and I had health coverage to avoid losing my entire retirement savings with one illness or injury. Medical bills are the leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the US and it is a common sight at petrol stations to see a donation box marked ‘Help Jimmy get his liver transplant’ and for churches to hold fundraisers to pay for surgery for one of their parishioners.

There are some stark and shocking differences between the UK and American healthcare systems. In the US, 45 million uninsured people play an ugly lottery where a sudden illness or injury may cost them a small or large fortune that they will have to pay off through bankruptcy or discharge over the rest of their lives. In the UK, the time from a patient determining with their GP that a treatment or procedure is the right one for the patient’s problem may be followed by months of waiting for the consultant’s/specialist’s appointment and agreement and then more months until actually undergoing the needed procedure. Bed shortages, cancelled appointments or shifts, and any inability on the patient’s part to attend a consultation or surgery date can further lengthen this delay. If a scarce radiological procedure is required prior to the surgery this can double the wait.

There are many other less concerning differences that it may be helpful or interesting to the UK and American medical community to compare and consider, but my ultimate conclusion is that the capitalist effect on American medical care of less government control and much more money, directed as patients and/or their insurers choose, in order to improve the care provided, leaves those Americans able to afford American medical care better off than the NHS patient. The NHS providing care for all may have a line for certain treatments but everyone in Britain is able to get into that line and no one is excluded from needed medical care. Therefore, the care provided by the NHS is much better than that received by the many Americans outside the health insurance system. Jennifer S Marsden

Reportage

انجمن پزشکان عمومی ایران پایگاه رسمی انجمن پزشکان عمومی ایران

انجمن پزشکان عمومی ایران پایگاه رسمی انجمن پزشکان عمومی ایران

این مقاله که تضعیف موقعیت پزشکان عمومی هست